Walking up the hill with my gear - hive tool, pollen patties, spare box of honey frames, I somehow knew. I’m not sure why I felt it but my suspicions were confirmed when I opened the lid of the hive and was met with only a scattering of dead bees in the inner cover. No gentle hum, no movement. I had lost them. A hive I had visited no more than a month ago, thriving, bustling.

After taking the hive apart and analyzing the signs - noting the food stores, the tiny cluster, the position of the bees, the quantity, I compare all this to what I have seen before, reasons I assume caused the loss. I also take note of things that I cannot explain. I will send some of the bees to the Beltsville Bee Lab in Maryland for testing, a free service that is offered to any beekeeper in the United States. But this year it will be interesting to see when I get data back. Not only because of large freezes happening with all research work in our country, but also because nationwide hive losses being reported this year have surpassed that of the Colony Collapse of 2006.

You read that right.

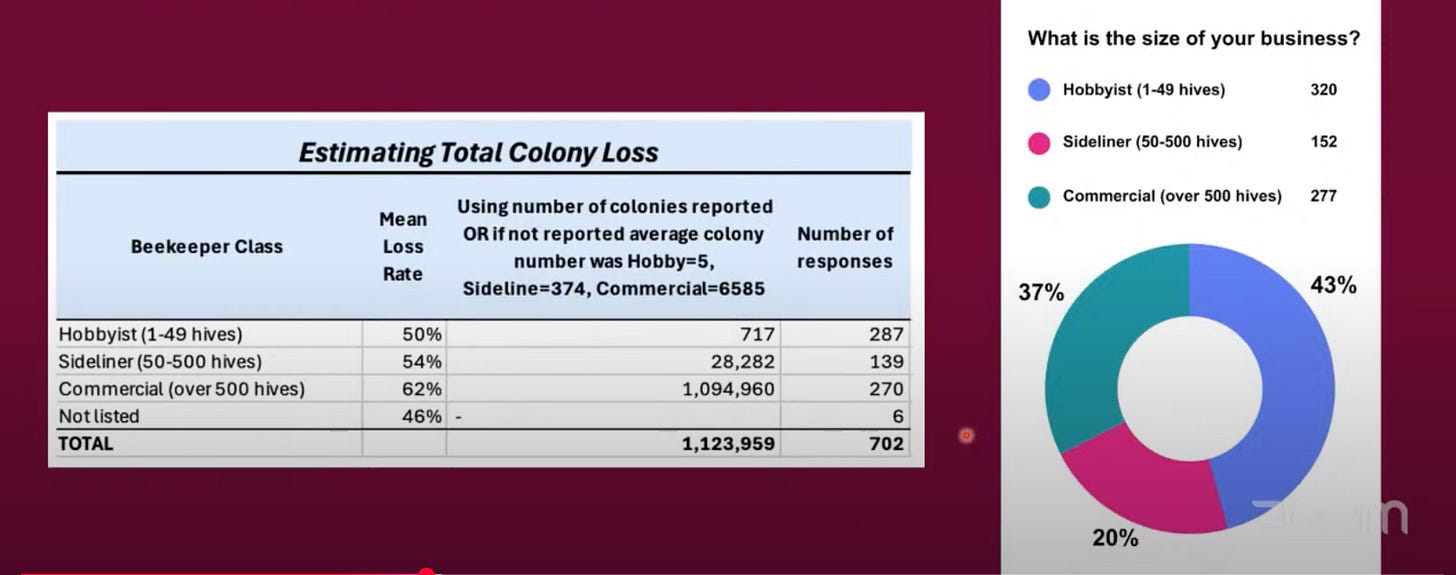

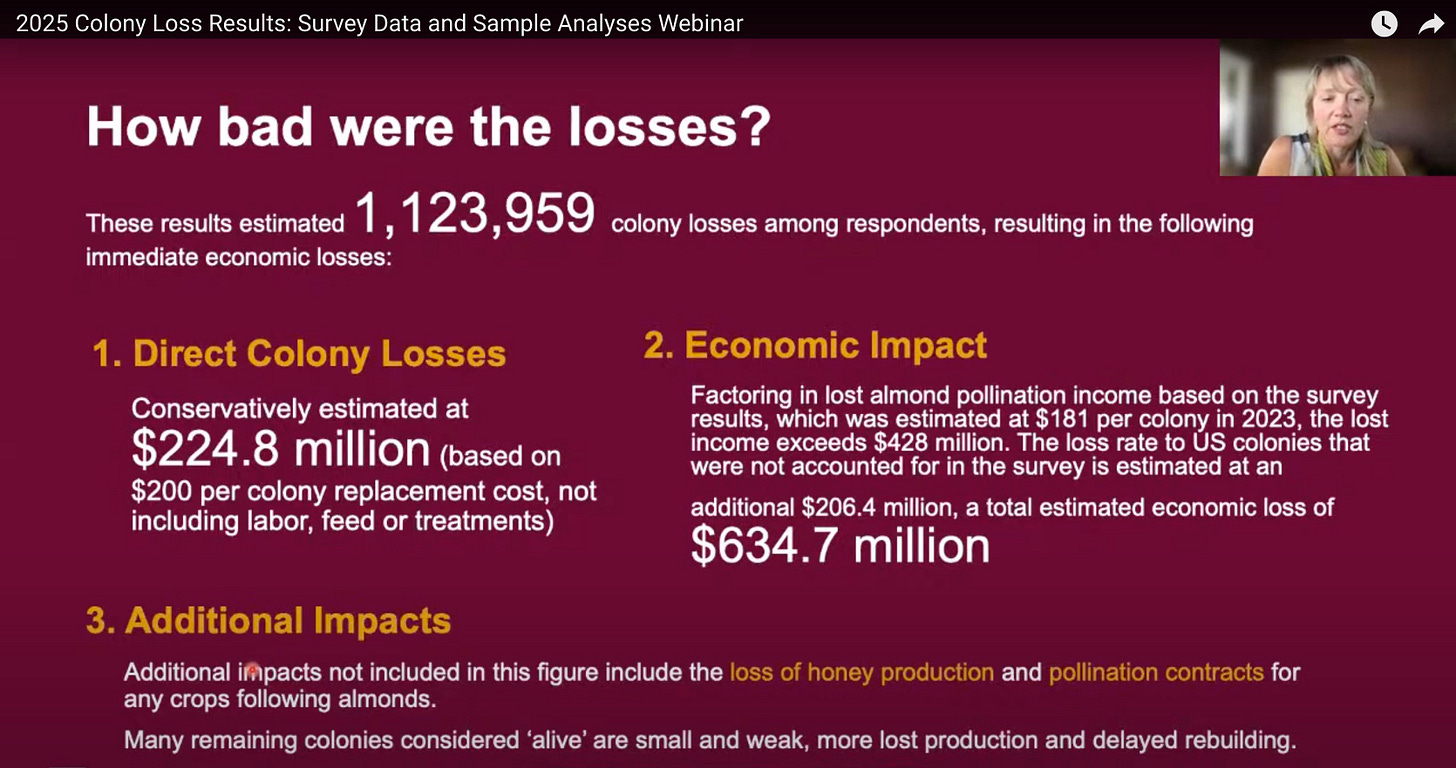

Hive loses this year are the highest they have been since we started keeping these comprehensive records in 2007.1

Each year, beekeepers lose hives for a myriad of reasons, though we have boiled it down to a few key issues:

loss of foraging habitat - this is diverse sources of pollen, nectar and resin that bees need to sustain a healthy diet

pesticide use - both how much and when pesticides are applied are huge factors

pests and diseases - there are critical pests in North America like the Varroa mite, and diseases they cause like Deformed Wing Virus, all of which severely weaken a colony, thus reducing their ability to survive the winter or grow efficiently.

Climate change - changing cycles of weather and timing of bloom periods are causing issues for bees to not only manage disease and access food, but reproduction cycles (mating, swarming) are having to change, and overlap is occurring with other species who are now competing for less food sources

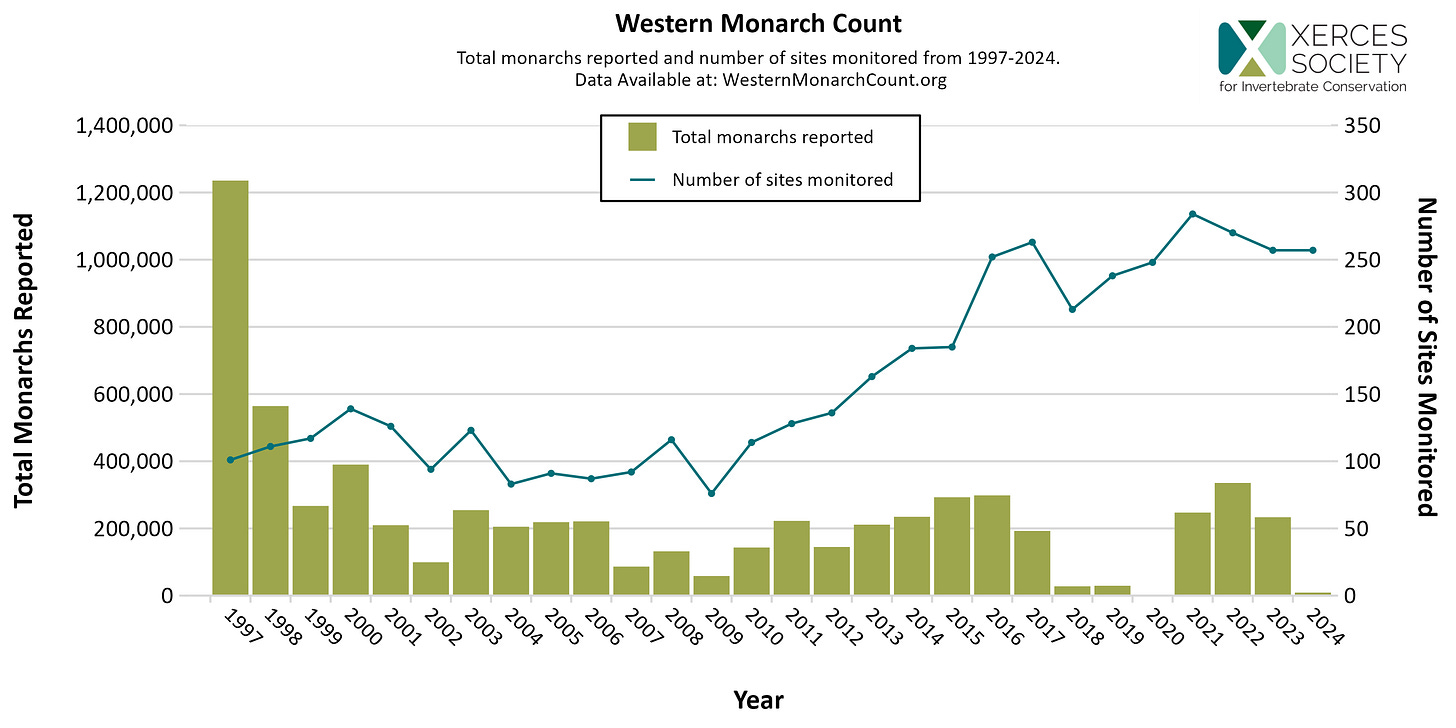

We know other pollinators are facing the same fate, likely because of similar reasons. Though studies are showing this years monarch numbers are slightly up, it is still drastically lower than ‘historic norms’ and citation notes habitat loss of both larval host plants and adult forage, and pesticide overuse to be key reasons for declines.

So What?

Well, I hate to sound alarmist, but this is a really big deal. And it’s a really big deal in two major ways.

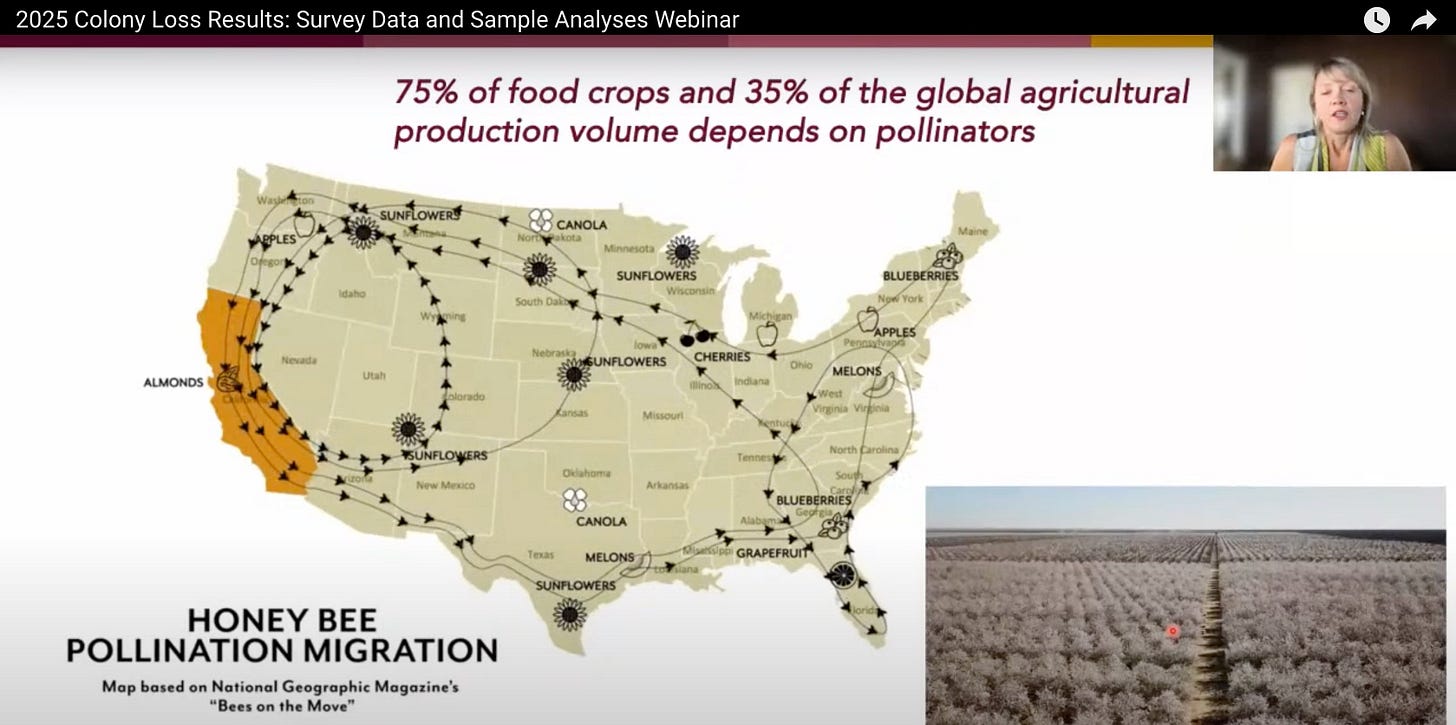

Because truly, I’m kind of talking about two different things: honey bees and pollinators. Its kind of like that ‘not all insects are bugs but all bugs are insects’ saying. Honey bees are pollinators, but not all pollinators are honey bees. And honey bees are not even native to the US, so, well, they are not even really native pollinators. It gets complicated though. In the United States we have developed a way of doing agriculture that relies on honey bees to pollinate. Migratory beekeeping allows large agricultural operations to bring in thousands to millions of hives to pollinate their crops to ensure the best yield. Migratory beekeepers move their bees around the country at different times of the season to pollinate different crops.

We know that honey bees do an amazing job at pollinating giant almond groves because they have something called floral fecundity. This means they focus on one flower at a time, one that will give them the biggest bang for their buck. So if dandelions and linden trees are both in bloom, they will be all over the linden and largely leave the dandelions alone. Why? Because the lindens nectar not only has a higher sugar content (= more energy) but there is a higher percentage of blooms in one spot, which means less travel time between flowers ( = more efficient foraging trip).

[All of this is not to say that honey bees only need a few things to survive. On the contrary. We know that honey bees, like us, need a varied diet with many different minerals, vitamins, amino acids etc for healthy function. They find these through a varied diet of different nectars and pollens as well as resins from trees. But I digress. More on this later]

But with these major losses, we are now facing possible pollination issues. With fewer hives pollinating the almonds, we have fewer almonds. We also have potentially even fewer hives that are ready and healthy enough to continue the trek around the country, so pollination services on a myriad of crops could mean lower pollination rates and lower production of many crop staples that require pollination.

So that’s the first reason it’s a really big deal. This has the ability to snowball as well. Because fewer hives means less bees to pollinate, but also a longer period of time necessary to build colony numbers back up. Which means missing pollinating any one of many crops. Or potentially going in to the fall with less colonies only to face more losses next year.

The second big reason is maybe a solution, except currently it isn’t any more promising. Native pollinators. We know there are a few natives that can act with exclusivity like the honey bee does - mason bees and bumblebees are being used in greenhouse pollination for example. But by and large, most pollinators forage on many flowers at once, which reduces the likelyhood of pollination. AND even if these insects could take the place of honey bees in major agricultural settings, they are facing the same issues as the honey bees, and the monoculture agriculture is even more detrimental to them. The only reason honey bees are sucessful for agriculture is because they get moved the minute the bloom is over. Otherwise it is just a sea of nothing for miles. No honey bee let alone most native pollinators can survive on one tree blooming for two to three weeks a year. And somehow we have created a situation where that is the fact.

I have been trying to think of a good way to end this article, but I really haven’t. I am a small scale keeper, who values each of my hives not only by the honey I can glean, but all the other unseen benefits. I know they are pollinating in my environment, helping the success of my neighbors blueberries and the wild roses that provide hips for countless hungry mouths in a time of scarcity. I also have a deep admiration and respect for them, as little tiny beings on this earth. Often, my time with the is meditative, and I am able to connect to something far beyond myself. Each loss I experience is felt wholeheartedly. Honey bees are not domesticated, like a pet. It is more like I am their steward, they are allowing me to be a part of their life, so when one is lost I feel like I failed them. And while I keep bees very differently than some, what are the effects for those that lost 1,000 hives, 10,000 hives this year?

I do think it is necessary to sit with this reality. To sit with the loss. Each one. I have solutions. I do. But I also want to truly take stock of where we are today.

And it is ripe with change.

For More Information:

Please Check out the Project Apis m webinar (about 1 hour) So Informational!

Here’s a shorter Ted talk from Marla Spivak (more than 10 years old, but still applies! Digestible and informational (and a sneak peek at what one of my solutions is)

Project Apis m preliminary analysis of the 2025 data that is still being collected but shows staggering numbers

Other Sources:

Giacobino, Agostina, et al. "Preliminary Results from the 2023-2024 US Beekeeping Survey: Colony Loss and Management."

“Honey bee colony losses reach ‘crisis’ level this year” by Kyle Odegard, Capital Press, published Feb 27, 2025

All research and opinions are my own

Oh my gosh! This is such major sorrowful news. I share some of your worries about the declining bee population.